Hamlet: Do you see the cloud over there that's almost the shape of a camel?

Polonius: By golly, it is like a camel, indeed.

Hamlet: I think it looks like a weasel.

Polonius: It is shaped like a weasel.

Hamlet: Or like a whale?

Polonius: It's totally like a whale.

A blog about politics, literature, humor, and drinking, with a liberal admixture of science trivia.

Tuesday, April 24, 2007

Sunday, April 22, 2007

It was fun while it lasted!

According to this story, nefarious and conspiratorial forces are working to bring down the Internet and replace with something scrubbed, sanitized, and in all ways denuded. If any anthropologists are reading this, I suggest you get those grant proposals in now before the greatest repository of humanity's symbolic unconscious is laid waste by the evil agents of decency, responsibility, and profit. The rest of you should torrent as much porn, illegally copied music, and Family Guy episodes as you can before the filth circus leaves town and all of us in tears.

Thursday, April 19, 2007

Burden of Proof - Has John Grisham written this one yet?

Gonzalez just told Charles Schumer that the "burden of proof" doesn't lie with him, it lies with those who make accusations. I think this was a big mistake. Not only did it risk stirring the ire of a senator from New York who calls himself "Chuck", but, for a putatively neutral government official, it's a statement made in bad faith. Gonzalez was obviously being evasive during the hearing, and that was bad enough. This sort of petty defensiveness, however, just reinforces the childish, clubhouse exclusivity that has long poisoned relations between the White House and its allies and the rest of the government. I mean, shouldn't these people be cooperating in a transparent manner? And Alberto has the gall to sit there and basically say "I'm not telling you anything! You think I did something wrong? Prove it!" Schumer, of course, was having none of it. "Sorry, buddy, but I don't have to prove anything. This isn't a trial. You may be a lawyer, but I'm a senator."

Gonzalez Tapdancing

Gonzalez is testifying on CSPAN right now -- looks like all of those cramming sessions worked out. My favorite: apparently, no one actually put names on the list of attorneys to be fired. It was a collective process without any direct assignments and no one responsible. Especially the AG.

UPDATE: Wow. Orrin Hatch gives great hea--committee. He gives meeting like a Bangkok councilman: enthusiastic, with lots of slobbering. Someone must have put the word out to close ranks.

Update 2: Gonzalez makes the mistake of interrupting Arlen Specter. And Specter breaks out the cane.

UPDATE: Wow. Orrin Hatch gives great hea--committee. He gives meeting like a Bangkok councilman: enthusiastic, with lots of slobbering. Someone must have put the word out to close ranks.

Update 2: Gonzalez makes the mistake of interrupting Arlen Specter. And Specter breaks out the cane.

Tuesday, April 17, 2007

A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Jedi

I recently bought a copy of the new Penguin edition of James Joyce's seminal work A Portrait of the Artist as a Young Man. Now, you can say much about a work of literature both by the epigraphs the author prefaces it with and the blurbs tacked onto the back cover by the publisher. In the former case, Joyce aligns himself squarely with tradition, however untraditional his writing may be, opening his narrative with a quote from Ovid: Et ignotas animum dimittit in artes (“And he brought forth his spirit into the unknown arts”). An almost Nietzschean line about the artist's creative potential (Ovid and Joyce both refer to a Daedalus)--this is hardly iconoclasm, though I suppose it captures that eternal jouissance we experience in youthful revolt.

The blurb, on the hand, really floored me:

"A truly extraordinary novel." -- Ewan McGregor

On the front cover. Now, we surely do not need Ewan McGregor to tell us that Joyce's work (novel?) is truly extraordinary. The informed reader knows this. At best, the blurb simply informs us that McGregor has read the book. But why is this such a powerful endorsement? Is it because McGregor still has youthful rebel cred leftover from Trainspotting, a film that embraces, if anything, more the spirit of creative nihilism than the transformative power of the artist (does its closing tagline, "choose life" get it off the hook)? Is it because the later McGregor sold his soul to the most banal cultural franchise in human history in order to extend his youth market shelflife? Do the publishers think fans of the Star Wars novelizations will be looking for something a bit meatier after downing all those hackneyed plots that float superficially around a vaguely Eastern, somewhat-Scientologist metaphysics? Finally, isn't it at least slightly noteworthy that Ewan McGregor isn't even Irish? And that if we're supposed to think he is (or is close enough), we'd also have to forget that Joyce spent most of his life in exile from Ireland and that much of his writing castigates his native society? So why a recommendation from an almost-authentically Irish person when Joyce was so critical of the authentically Irish? I think the real answer, as always, lies with one man: Sean Connery. Fans of McGregor, the same ones who pick up Joyce in the bookstore, will remember his repudiation of his fellow Scotsman as a narrow-minded, nationalistic hypocrite. Like Joyce, McGregor is able to be a scathing commentator on his own culture while at the same time being one of its most prominent symbols. The connection will not be lost on a generation raised by the odd combination of stylized violence/glamorized drug addiction and treacly fantasy-adventure stories that comprise contemporary entertainment. And, after all, the guy still does full frontal nudity (like Harry Potter!), and that's bound to shock at least a few people yet, quite in the tradition of softporn Ulysses. McGregor has also taught us that you can be a tool of the mainstream media-culture syndicate and still retain a marginal identity--this, after all, is the true dream of the modern subject: being different, misunderstood, and the focus of everybody else's obsessive attention. Rather like Joyce, and Portrait, now available from Penguin, a truly extraordinary novel.

The blurb, on the hand, really floored me:

"A truly extraordinary novel." -- Ewan McGregor

On the front cover. Now, we surely do not need Ewan McGregor to tell us that Joyce's work (novel?) is truly extraordinary. The informed reader knows this. At best, the blurb simply informs us that McGregor has read the book. But why is this such a powerful endorsement? Is it because McGregor still has youthful rebel cred leftover from Trainspotting, a film that embraces, if anything, more the spirit of creative nihilism than the transformative power of the artist (does its closing tagline, "choose life" get it off the hook)? Is it because the later McGregor sold his soul to the most banal cultural franchise in human history in order to extend his youth market shelflife? Do the publishers think fans of the Star Wars novelizations will be looking for something a bit meatier after downing all those hackneyed plots that float superficially around a vaguely Eastern, somewhat-Scientologist metaphysics? Finally, isn't it at least slightly noteworthy that Ewan McGregor isn't even Irish? And that if we're supposed to think he is (or is close enough), we'd also have to forget that Joyce spent most of his life in exile from Ireland and that much of his writing castigates his native society? So why a recommendation from an almost-authentically Irish person when Joyce was so critical of the authentically Irish? I think the real answer, as always, lies with one man: Sean Connery. Fans of McGregor, the same ones who pick up Joyce in the bookstore, will remember his repudiation of his fellow Scotsman as a narrow-minded, nationalistic hypocrite. Like Joyce, McGregor is able to be a scathing commentator on his own culture while at the same time being one of its most prominent symbols. The connection will not be lost on a generation raised by the odd combination of stylized violence/glamorized drug addiction and treacly fantasy-adventure stories that comprise contemporary entertainment. And, after all, the guy still does full frontal nudity (like Harry Potter!), and that's bound to shock at least a few people yet, quite in the tradition of softporn Ulysses. McGregor has also taught us that you can be a tool of the mainstream media-culture syndicate and still retain a marginal identity--this, after all, is the true dream of the modern subject: being different, misunderstood, and the focus of everybody else's obsessive attention. Rather like Joyce, and Portrait, now available from Penguin, a truly extraordinary novel.

Monday, April 16, 2007

T. G. I. M.

It may be that Monday has the highest average rate of heartattacks, but the weekends are slow news and blog days. Now that the work week is back, we return to the gripping "he said ... she said" stories that constitute political coverage: "Republicans are sounding down in the dumps ... Dems say bring it on." I'm just waiting for "Republicans advise caution ... Dems say Get 'er done."

It may be that Monday has the highest average rate of heartattacks, but the weekends are slow news and blog days. Now that the work week is back, we return to the gripping "he said ... she said" stories that constitute political coverage: "Republicans are sounding down in the dumps ... Dems say bring it on." I'm just waiting for "Republicans advise caution ... Dems say Get 'er done."Tipplometer: lets make that five commiserating drams of Wild Turkey for distraught repubs, and a jack and tobasco shot for the dems. Tipplometer total: 6.0

E. T. Rigged It

File this under novel reasons for losing an election (News of the Wierd):

A federal appeals court in March turned down Ruth Parks' challenge to her re-election loss in 2001 as the recorder-treasurer of Horseshoe Bend, Ark., which she blamed on a conspiracy by the mayor and police chief. The court concluded that voters, not a conspiracy, had defeated her, perhaps because of the prominence of her belief in UFOs and the conflicting views of her and her husband as to whether she personally had ever been abducted by aliens: She said she hadn't, but her husband said she had, many times, and that the aliens had left scars. [WMC-TV (Memphis)-AP, 3-15-07]

For the lawyers out there: would that be grounds for divorce?

A federal appeals court in March turned down Ruth Parks' challenge to her re-election loss in 2001 as the recorder-treasurer of Horseshoe Bend, Ark., which she blamed on a conspiracy by the mayor and police chief. The court concluded that voters, not a conspiracy, had defeated her, perhaps because of the prominence of her belief in UFOs and the conflicting views of her and her husband as to whether she personally had ever been abducted by aliens: She said she hadn't, but her husband said she had, many times, and that the aliens had left scars. [WMC-TV (Memphis)-AP, 3-15-07]

For the lawyers out there: would that be grounds for divorce?

Writers we get over

Jessa Crispin, over at "Bookslut," puts her finger on my failure to jump on the Vonnegut for canonization train [correction -- Crispin links this back to an Op-ed by Verlyn Klinkenborg at the NYTimes. But do visit Bookslut.]:

If you read Kurt Vonnegut when you were young — read all there was of him, book after book as fast as you could the way so many of us did — you probably set him aside long ago. That’s the way it goes with writers we love when we’re young. It’s almost as though their books absorbed some part of our DNA while we were reading them, and rereading them means revisiting a version of ourselves we may no longer remember or trust.

For me, the writer that epitomizes this would be Ayn Rand. People who were exposed to Rand early enough are able to continue growing up; but those who fall for Rand too late in life (read college) end up permanently stunted. Rand is a bit like The Transformers. Awesome when you're young, and fun to look back on nostalgically (remember the movie version w/ Orson Welles and Judd Nelson? Rad.). But if you're still carrying the lunchbox or wearing the underwear, you've got problems.

If you read Kurt Vonnegut when you were young — read all there was of him, book after book as fast as you could the way so many of us did — you probably set him aside long ago. That’s the way it goes with writers we love when we’re young. It’s almost as though their books absorbed some part of our DNA while we were reading them, and rereading them means revisiting a version of ourselves we may no longer remember or trust.

For me, the writer that epitomizes this would be Ayn Rand. People who were exposed to Rand early enough are able to continue growing up; but those who fall for Rand too late in life (read college) end up permanently stunted. Rand is a bit like The Transformers. Awesome when you're young, and fun to look back on nostalgically (remember the movie version w/ Orson Welles and Judd Nelson? Rad.). But if you're still carrying the lunchbox or wearing the underwear, you've got problems.

Meet The Steve

Steve (who posted below) is our philosophe résidant and foreign correspondent. Right now he's living in Japan and making arrangements (hiring shirpas, storing canned meats, using the stair climber) for his round the world trip, which starts in August. Besides keeping up the intellectual tone of our discussions, Steve will serving up reflections on the natural genius of the places he visits. Domo.

Steve (who posted below) is our philosophe résidant and foreign correspondent. Right now he's living in Japan and making arrangements (hiring shirpas, storing canned meats, using the stair climber) for his round the world trip, which starts in August. Besides keeping up the intellectual tone of our discussions, Steve will serving up reflections on the natural genius of the places he visits. Domo.

Sunday, April 15, 2007

Tipplometer: Blue Sunday

We're going to assume that Pennsylvania Ave. is strictly observing the sabbath -- the Tipplometer plunged today to a one. (Only godless heathens such as myself would be sipping their Jameson's right now.) Don't worry, with Congress back in session and its leaders heading to the Oval Office this week, I'm expecting a surge around happy hour tomorrow.

Saturday, April 14, 2007

Jouez-l'encore, Hirohito

Those who still derive amusement from examples of history repeating itself will be delighted by a story published today in Le Monde under the heading "Opération kamikaze à Casablanca et nouvelles arrestations." You do not even have to read the story. The headline alone, with its combination of French, Japanese, and classic Hollywood elements, evokes a certain sentimentality, proving that history is rather like a food processor: surely, its mechanical action is repetitive, but you can never predict what unassimilated lumps its churnings will toss up as the multitudinous ingredients are puréed.

Isn't it fascinating that "suicide bomber" is rendered here in French with "kamikaze"? Of course, the English expression is as new as the French adoption from Japanese. Suicide, already a disturbing act against oneself, is combined with an external, devastating attack on others. This surrendering to the negativity of self-destruction by means of a positive assault on the environment that produced it might be considered postmodern. "I recognize my subject position abstractly, but I reject it, and further, I seek to destroy the enforcers of subject positions themselves." There were martyrs in the past who sacrificed themselves for a higher cause, but weren't they somehow different? The word "martyr" literally means witness, and it was the positive fact of the victim's individual, witnessing identity that lent significance, gravitas even, to his or her death, the positive result of which is the martyr's inscription into history. Perhaps we can respect this. A suicide bombing, however, seems an extreme self-abnegation. The perpetrators, in their willingness to be erased from history, commit not only physical violence against us, but even more inexcusably, they offend our reverence for the priority of the individual. It is, after all, on behalf of individual rights and freedoms that the West always claims to fight. From this perspective, anyone who makes such a pointless sacrifice, who becomes the anonymous instrument of others, must perforce be evil.

But this is where French wisdom shows itself. The word "kamikaze", meaning "divine wind", actually preserves the dignity of the erstwhile "bomber". Many of our ideas about the limits of human malice derive from World War II, and the kamikaze, the insane agent of a relentless and unfathomable Asian enemy, is one of the most profound. The niggling cultural differences that seem an almost aesthetic concern today remain at the heart of human fear. If we certainly recognize in one another a common humanity, what do we make of fellow humans who do things we would never consider, who go farther than we would? Is our fear for our own destruction at the hands of such enemies or for the more terrifying possibility that "we" are not so unlike "them"? The original divine wind was the one that sent the Monguls packing after repeated attempts to invade Japan. This grace, almost exclusive to Japan in the era of the Khans, may explain the feeling that famously developed among Japanese that they are an exceptional people, unconquered and (as a result) unmixed. This divine election also meant they felt destined to lead the other nations of Asia (they were already trying to conquer Korea in the 16th century). But a nationalistic superiority complex is not just a peculiarity of imperial island nations. Our own adventures in the Middle East, if they really are predicated on a democracy-building program, reflect an American superiority complex just as devastating as Japan's. The idea of a Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere is surely no more farcical than a Coalition of the Willing. And however cruel was Japan's imperial embrace in practice, you can hardly fault their motives: against an overbearing and exploitative West, Japan intended to rise up and loose the shackles Europe had placed on the nations of Asia. When you actually believe your way of life is the best one there is, how can you morally prevent others from enjoying it? Why wouldn't you force them to conform to it, for their own good? And thus you had the incongruous image of Javanese women practicing karate at dawn. And, ultimately, fighter pilots who were willing to die, not just on behalf of an emperor they never met, but however tenuously, for the greater good of humanity.

Except we won that one. And so today the greater good of humanity seems to mean the greater good of the United States and its allies. We were an isolationist nation before World War II. Did we achieve victory then only to adopt the aspirations of our enemies? We are again confronted by an enemy who exposes to us our own dark side. They consider themselves the favored of God, their very bodies the instrument of a divine wind. That wind is not the product of an esoteric evil but the necessity of a conviction that would spread its benevolence to all of humanity. What divine wind is at our backs, driving us? If there isn't one, by what right do we storm across the world and what claim can we possibly have on its sympathy? By relegating suicide bombers, the kamikaze of today, to the amorphous realm of evil, we fail to understand that their mission is quite similar to our own. The difference lies in the means to carry it out. The French surely have little nostalgia for their own colonial adventures, though we have it on their behalf for all those Casablancas that somebody else controlled, where somebody else did the dirty work, while we pretended to be everybody's heroes. In the future, we may have a nostalgia of a different sort: for a time when we could more easily draw moral boundaries, when we at least had the luxury of knowing where our enemy lived before he moved closer to home.

Isn't it fascinating that "suicide bomber" is rendered here in French with "kamikaze"? Of course, the English expression is as new as the French adoption from Japanese. Suicide, already a disturbing act against oneself, is combined with an external, devastating attack on others. This surrendering to the negativity of self-destruction by means of a positive assault on the environment that produced it might be considered postmodern. "I recognize my subject position abstractly, but I reject it, and further, I seek to destroy the enforcers of subject positions themselves." There were martyrs in the past who sacrificed themselves for a higher cause, but weren't they somehow different? The word "martyr" literally means witness, and it was the positive fact of the victim's individual, witnessing identity that lent significance, gravitas even, to his or her death, the positive result of which is the martyr's inscription into history. Perhaps we can respect this. A suicide bombing, however, seems an extreme self-abnegation. The perpetrators, in their willingness to be erased from history, commit not only physical violence against us, but even more inexcusably, they offend our reverence for the priority of the individual. It is, after all, on behalf of individual rights and freedoms that the West always claims to fight. From this perspective, anyone who makes such a pointless sacrifice, who becomes the anonymous instrument of others, must perforce be evil.

But this is where French wisdom shows itself. The word "kamikaze", meaning "divine wind", actually preserves the dignity of the erstwhile "bomber". Many of our ideas about the limits of human malice derive from World War II, and the kamikaze, the insane agent of a relentless and unfathomable Asian enemy, is one of the most profound. The niggling cultural differences that seem an almost aesthetic concern today remain at the heart of human fear. If we certainly recognize in one another a common humanity, what do we make of fellow humans who do things we would never consider, who go farther than we would? Is our fear for our own destruction at the hands of such enemies or for the more terrifying possibility that "we" are not so unlike "them"? The original divine wind was the one that sent the Monguls packing after repeated attempts to invade Japan. This grace, almost exclusive to Japan in the era of the Khans, may explain the feeling that famously developed among Japanese that they are an exceptional people, unconquered and (as a result) unmixed. This divine election also meant they felt destined to lead the other nations of Asia (they were already trying to conquer Korea in the 16th century). But a nationalistic superiority complex is not just a peculiarity of imperial island nations. Our own adventures in the Middle East, if they really are predicated on a democracy-building program, reflect an American superiority complex just as devastating as Japan's. The idea of a Greater East Asia Co-prosperity Sphere is surely no more farcical than a Coalition of the Willing. And however cruel was Japan's imperial embrace in practice, you can hardly fault their motives: against an overbearing and exploitative West, Japan intended to rise up and loose the shackles Europe had placed on the nations of Asia. When you actually believe your way of life is the best one there is, how can you morally prevent others from enjoying it? Why wouldn't you force them to conform to it, for their own good? And thus you had the incongruous image of Javanese women practicing karate at dawn. And, ultimately, fighter pilots who were willing to die, not just on behalf of an emperor they never met, but however tenuously, for the greater good of humanity.

Except we won that one. And so today the greater good of humanity seems to mean the greater good of the United States and its allies. We were an isolationist nation before World War II. Did we achieve victory then only to adopt the aspirations of our enemies? We are again confronted by an enemy who exposes to us our own dark side. They consider themselves the favored of God, their very bodies the instrument of a divine wind. That wind is not the product of an esoteric evil but the necessity of a conviction that would spread its benevolence to all of humanity. What divine wind is at our backs, driving us? If there isn't one, by what right do we storm across the world and what claim can we possibly have on its sympathy? By relegating suicide bombers, the kamikaze of today, to the amorphous realm of evil, we fail to understand that their mission is quite similar to our own. The difference lies in the means to carry it out. The French surely have little nostalgia for their own colonial adventures, though we have it on their behalf for all those Casablancas that somebody else controlled, where somebody else did the dirty work, while we pretended to be everybody's heroes. In the future, we may have a nostalgia of a different sort: for a time when we could more easily draw moral boundaries, when we at least had the luxury of knowing where our enemy lived before he moved closer to home.

A word on mixology

Did you know drinking cocktails was patriotic? It turns out that the cocktail is quintessentially American; the word emerged in the U.S. in the early nineteenth century, and the form of the libation -- hard liquor mixed with some kind of sweetener, gained prominence here first, as well. Cocktails were developed because there was lots of nasty hooch being brewed here, and people wanted something to sweeten the flavor. But the event which really launched the cocktail was prohibition. When alcohol became illegal, it was a lot easier to smuggle a fifth of gin than a barrel of beer. As a result, the American brewing industry tanked, and the mixologist was born. So feel free to sneer at those servile imitators, the microbrews, next time you savor a mint julep or its southern cousin, the mohito. And hum a few bars of your favorite stars and stripes-themed tune -- it's the American way.

Apologia pro bloga sua

It's a year old, but I thought I'd include the clip which fomented the idea for this blog. May your glass be ever full, and may you be in heaven half an hour before the devil knows you're dead! (clink)

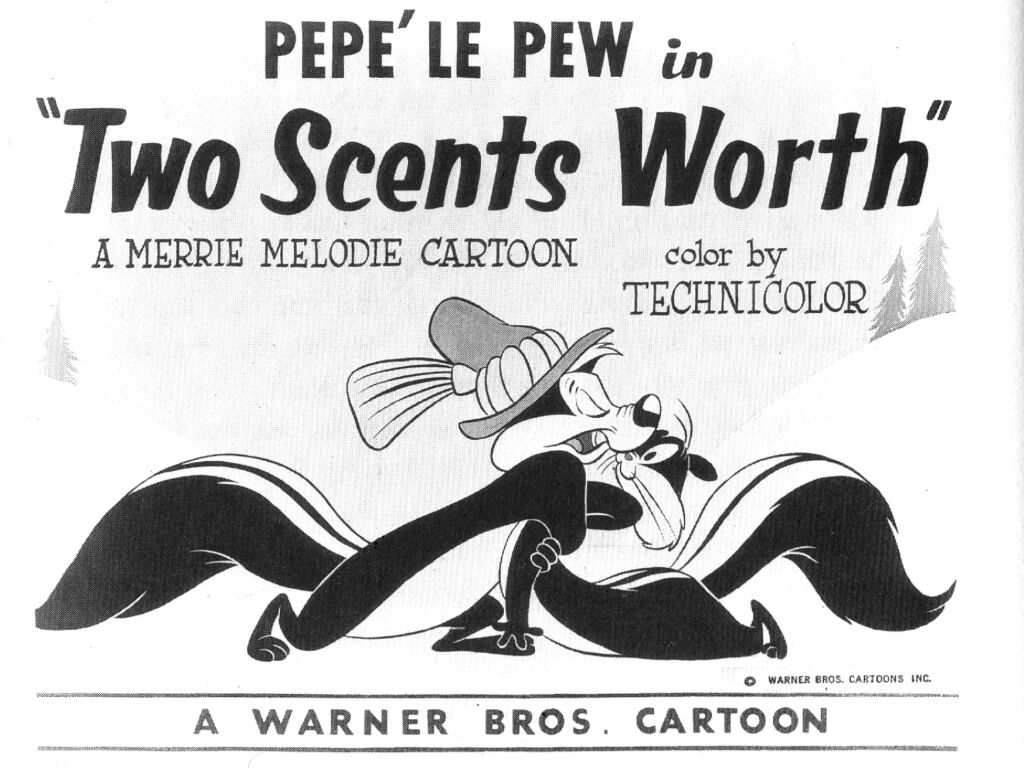

Cats and Skunks

Mentioning Pepe Le Pew's hijinx got me wondering how closely related cats and skunks are. And it turns out: pretty close (links to a powerpoint presentation from a textbook). Skunks (Mephitis mephitis) are part of the family of mustelids, which are the nearest family to felidae, including the domestic housecat (Felis catus). They're also closer in relation to puppys (canids) than cats are, which perhaps explains why I've heard they make great pets (if stink gland is removed). Not an experiment I'll be trying any time soon. And by way of correction to what's below, it seems that it was the cat who was accidentally painted to look like Le Pew's smelly paramour, not the other way around.

Rhetoric and Framing

[Links fixed] Over at "Adventures in Ethics and Science," Janet Stemwedel has a post on the slippery concept of "framing" and how students understand their education. She links back to a larger discussion about framing -- including Coturnix's remarks on what it is, how it works, etc., over at "A blog around the clock."

This raises a big issue for me: the relationship between particular expressions and truth. When Lakoff starting making big noise in democratic circles during the run up to the 2004 elections (if I recall correctly) it was because he offered a neat way to explain the unity of the republican message machine versus the confusion of the democratic, as well as a "so easy, even a child could do it" method for fixing this problem: framing. Republicans, apparently, were good at it, Democrats were not -- but they could learn.

But if you read Lakoff's work, it's hard to tell what the difference is between Lakoff's framing and rhetorical tropes. There's little in his analysis that improves upon any solid 18th-C work on rhetoric, for instance, George Campbell's Philosophy of Rhetoric, or Hugh Blair's Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. In fact, Campbell and Blair, it seems to me, are more sophisticated, insofar as they give significant attention to immediate context and expression. Allow me to explain.

For Lakoff, the context and expression are not important -- it doesn't matter how the "frame" is expressed, or exactly where it occurs in a passage/speech. I'm sure he pays lip-service to at least the latter somewhere, but if you read his analysis, it is completely ignored. In my favorite examples from Metaphors we Live By (as I recall), Lakoff breaks down a joke which was apparently prevalent in the late nineties after the Lewinski/impeachment thing: "If Clinton were the titanic, the iceberg would sink." Lakoff breaks this down into a "frame" -- the Titanic and its crash with the iceberg, and its content, the Clinton scandal, with the impeachment process and associated events. He then maps the substitution between various terms; Clinton, obviously, fulfills the place of the titanic in the frame, the impeachment, the iceberg. But the pressure of the Clinton situation -- in which the impeachment failed -- makes the "iceberg/impeachment" sink within the Titanic frame. (As usual, there's nothing that kills a good joke like breaking it down.)

What I love about Lakoff's example, is that it ignores the necessary dependence of the joke on its humor, and the dependence of humor upon the particular expression. For instance, it's much less funny to put the punch line first: "The iceberg would sink, if Clinton were the titanic," or an even more tortuous, "The iceberg that sunk the titanic would sink if the titanic were Clinton and represented the impeachment." According to Lakoff's analysis, these all say the same thing, because they have the same content. But I think you'll agree that they don't work the same way. Moreover, it would make a huge difference what the larger context of the joke was. Is it a Democratic rally, in which it (presumably) inspires us with confidence in a manifest destiny of the Democratic party? Or is it a Republican fundraiser, calculated to inspire donors with the gravity of the challenge to be overcome through an equally deep digging into their pockets? Or is it a discussion between businessmen in Hong Kong, in which it might entail reference to his huge global stature, as well, perhaps, as an implicit commentary on the impending end of British rule? The last might be a stretch, but I think the significance of context should be clear here.

And that's why I think Blair and Campbell are more sophisticated in their thinking. They discuss metaphor, analogy, and simile, but balance this focused discussion of tropes with a heavy emphasis upon context -- how the tropes relates to what came before or after, when to use one, how to adjust it to the context of a specific speech or audience.

Lakoff's popularity is due, I think, to its translation into a pseudo-cognitive science vocabulary, our old rhetorical friend the trope. Whereas someone might off-hand dismiss tropes as "mere rhetoric," they are less likely to dismiss this totally new idea of "framing" that a professor of linguistics at Berkley developed. For one, I'd love to hear how "framing" is different from the vehicle/tenor distinction employed by earlier theorizers of metaphor. Of course, Lakoff does put far more emphasis upon metaphor than characterizes earlier rhetorical thinkers -- he sees thought itself as inherently metaphorical. (Although, again, I'm not sure how this is different from the analogical/associative underpinnings of thought in much enlightenment philosophy, from Hume on.) But Lakoff, it seems to me, misses the big picture insofar as he turns us away from looking at actual, particular language use.

The discomfort of many with the idea of "framing" is not, as some have suggested, that it gives us a sense of being forced into thinking a certain way ("framed"). It is rather the way in which Lakoff's framing invokes all of our deeply-held anxieties about rhetoric in language, anxieties rooted in (1) the belief that there is a division between "ideas" that are language independent and the language we use to "express" them, and (2) that this divorce between language and ideas equals a divorce between language and truth, and (3) that the divorce between language and truth means that some bad people might manipulate language to convince us of things that are not true. Regardless of the validity of these beliefs, all of them are the product of rhetorical models of language as they developed from the classical period through the present day (though that's an argument I can't make right now). And that means that Lakoff, by "framing" rhetorical tropes in a way that doesn't seem rhetorical, has brought us to revisit the conflicts between persuading, convincing, and communicating that led us to drop rhetoric in the first place. To analogize to Pepe le Pieu (for whom, btw, I have a fondness), you can repaint a skunk so it looks like a cat -- but it's still a skunk. [Correction: It's Pepe le Pew, and it was a cat who kept getting painted as a skunk, not the other way around.]

This raises a big issue for me: the relationship between particular expressions and truth. When Lakoff starting making big noise in democratic circles during the run up to the 2004 elections (if I recall correctly) it was because he offered a neat way to explain the unity of the republican message machine versus the confusion of the democratic, as well as a "so easy, even a child could do it" method for fixing this problem: framing. Republicans, apparently, were good at it, Democrats were not -- but they could learn.

But if you read Lakoff's work, it's hard to tell what the difference is between Lakoff's framing and rhetorical tropes. There's little in his analysis that improves upon any solid 18th-C work on rhetoric, for instance, George Campbell's Philosophy of Rhetoric, or Hugh Blair's Lectures on Rhetoric and Belles Lettres. In fact, Campbell and Blair, it seems to me, are more sophisticated, insofar as they give significant attention to immediate context and expression. Allow me to explain.

For Lakoff, the context and expression are not important -- it doesn't matter how the "frame" is expressed, or exactly where it occurs in a passage/speech. I'm sure he pays lip-service to at least the latter somewhere, but if you read his analysis, it is completely ignored. In my favorite examples from Metaphors we Live By (as I recall), Lakoff breaks down a joke which was apparently prevalent in the late nineties after the Lewinski/impeachment thing: "If Clinton were the titanic, the iceberg would sink." Lakoff breaks this down into a "frame" -- the Titanic and its crash with the iceberg, and its content, the Clinton scandal, with the impeachment process and associated events. He then maps the substitution between various terms; Clinton, obviously, fulfills the place of the titanic in the frame, the impeachment, the iceberg. But the pressure of the Clinton situation -- in which the impeachment failed -- makes the "iceberg/impeachment" sink within the Titanic frame. (As usual, there's nothing that kills a good joke like breaking it down.)

What I love about Lakoff's example, is that it ignores the necessary dependence of the joke on its humor, and the dependence of humor upon the particular expression. For instance, it's much less funny to put the punch line first: "The iceberg would sink, if Clinton were the titanic," or an even more tortuous, "The iceberg that sunk the titanic would sink if the titanic were Clinton and represented the impeachment." According to Lakoff's analysis, these all say the same thing, because they have the same content. But I think you'll agree that they don't work the same way. Moreover, it would make a huge difference what the larger context of the joke was. Is it a Democratic rally, in which it (presumably) inspires us with confidence in a manifest destiny of the Democratic party? Or is it a Republican fundraiser, calculated to inspire donors with the gravity of the challenge to be overcome through an equally deep digging into their pockets? Or is it a discussion between businessmen in Hong Kong, in which it might entail reference to his huge global stature, as well, perhaps, as an implicit commentary on the impending end of British rule? The last might be a stretch, but I think the significance of context should be clear here.

And that's why I think Blair and Campbell are more sophisticated in their thinking. They discuss metaphor, analogy, and simile, but balance this focused discussion of tropes with a heavy emphasis upon context -- how the tropes relates to what came before or after, when to use one, how to adjust it to the context of a specific speech or audience.

Lakoff's popularity is due, I think, to its translation into a pseudo-cognitive science vocabulary, our old rhetorical friend the trope. Whereas someone might off-hand dismiss tropes as "mere rhetoric," they are less likely to dismiss this totally new idea of "framing" that a professor of linguistics at Berkley developed. For one, I'd love to hear how "framing" is different from the vehicle/tenor distinction employed by earlier theorizers of metaphor. Of course, Lakoff does put far more emphasis upon metaphor than characterizes earlier rhetorical thinkers -- he sees thought itself as inherently metaphorical. (Although, again, I'm not sure how this is different from the analogical/associative underpinnings of thought in much enlightenment philosophy, from Hume on.) But Lakoff, it seems to me, misses the big picture insofar as he turns us away from looking at actual, particular language use.

The discomfort of many with the idea of "framing" is not, as some have suggested, that it gives us a sense of being forced into thinking a certain way ("framed"). It is rather the way in which Lakoff's framing invokes all of our deeply-held anxieties about rhetoric in language, anxieties rooted in (1) the belief that there is a division between "ideas" that are language independent and the language we use to "express" them, and (2) that this divorce between language and ideas equals a divorce between language and truth, and (3) that the divorce between language and truth means that some bad people might manipulate language to convince us of things that are not true. Regardless of the validity of these beliefs, all of them are the product of rhetorical models of language as they developed from the classical period through the present day (though that's an argument I can't make right now). And that means that Lakoff, by "framing" rhetorical tropes in a way that doesn't seem rhetorical, has brought us to revisit the conflicts between persuading, convincing, and communicating that led us to drop rhetoric in the first place. To analogize to Pepe le Pieu (for whom, btw, I have a fondness), you can repaint a skunk so it looks like a cat -- but it's still a skunk. [Correction: It's Pepe le Pew, and it was a cat who kept getting painted as a skunk, not the other way around.]

Friday, April 13, 2007

Gov. Corzine in Hospital

Not everyone's a huge fan of Jon Corzine. I only met him once (at a rally, while going door-to-door for him during his last campaign), but he's always struck me as an honest and hugely sincere politician. And he's respected on both sides of the isle in New Jersey; I had a long conversation with an aide to one of the former governors last November, who was excited about the future. He said Corzine was able to galvanize enough support to fix some of New Jersey's looming problems (in particular a huge budget deficit generated by a series of tax-slashing republican governors -- see post below on "Reaganomics"). And he handled the previous budget standoff with aplomb. I'm watching anxiously, hoping that he'll pull through. I don't know if there's any secular "power of hope," but in case there is, send some hope-juju his way, too.

Introducing the Tipplometer

The Tipplometer is a Swiss-calibrated ethyl alcohol sensor that accurately assesses the approximate magnitude of the bender its current subject is on. For now and the foreseeable future, this Tipplometer will be tied into the wet bar behind the leather-bound "Great Books" collection in the Oval Office. The majesty of the device is its elegant summation of the current standoff between the White House and Congress over the Defense Appropriations Bill (which has all of the impetus of the tractor-mounted game of "chicken" in Footloose). Tipplometer's reading: One bourbon, one shot, and five beers.

Reaganomics

I've always wondered: if you assembled a hundred respected economists in a room, and asked them whether trickle-down economics worked, what would they say? Unsurprisingly, this turns out to be a silly question. Brad DeLong (who likes to do the economics at Berkeley) weighs in. Briefly, Bruce Bartlett recently wrote a piece on the subject for the NYTimes, and it's sparked a debate about how supply-side economics was taught in the 70's and 80's. The occasion for this discussion, I suspect, has less to do with the current political climate, than with a general re-evaluation following Milton Friedman's death last year. But the punch is that most economists, of any stripe, seem to agree that some supply side adjustments are valuable, like lowering high marginal tax rates. But apparently, this limited, if hard-fought discussion within economics has metastasized, so that conservatives now believe any reduction in tax rates of any kind will spur economic growth.

The other side of the coin is fiscal policy -- the belief that monetary adjustments (read the Fed's interest-rate jiggering) could affect factors from pricing to employment. As with the supply-side school of thought, this policy could be taken too far, and is often credited with the "stagflation" of the 1970's, when attempts to adjust production through fiscal policy resulted in an increase in inflation without an increase in economic growth. In reading DeLong's post, along with the comments posted by various economists, it seems that the consensus is both policies should be applied, in moderation. Supply-side adjustments are useful in spurring growth when inflation seems to be looming, but it takes a long time to kick in and should be targeted to specific taxes; monetary adjustments are faster-acting but cannot stem inflation on their own. Believe it or not, the solution seems to be careful adjustment of policy to the economic climate. Shocker.

I guess it's no surprise that these discussions don't appear on Meet the Press, but it sure is nice when the experts collect to hash something out.

The other side of the coin is fiscal policy -- the belief that monetary adjustments (read the Fed's interest-rate jiggering) could affect factors from pricing to employment. As with the supply-side school of thought, this policy could be taken too far, and is often credited with the "stagflation" of the 1970's, when attempts to adjust production through fiscal policy resulted in an increase in inflation without an increase in economic growth. In reading DeLong's post, along with the comments posted by various economists, it seems that the consensus is both policies should be applied, in moderation. Supply-side adjustments are useful in spurring growth when inflation seems to be looming, but it takes a long time to kick in and should be targeted to specific taxes; monetary adjustments are faster-acting but cannot stem inflation on their own. Believe it or not, the solution seems to be careful adjustment of policy to the economic climate. Shocker.

I guess it's no surprise that these discussions don't appear on Meet the Press, but it sure is nice when the experts collect to hash something out.

Inaugural Post

Welcome to a poorly-conceived pet project. I'm under the gun right now, trying to scribble out the rest of my dissertation in delusive hope of landing a (cough) job. Which means it's a perfect time to indulge in a long-held desire: launching a blog in which to bloviate on whatever topic catches my eye, in a manner both less-practiced and less original than others squeezing their way through this tubular environment. Because I've had some contact with journalism, politics, and science, as well as the literature which I now study, this blog is liable to range. I'm also likely to invite others to post once in a while; I hope to assemble a broad buffet of over-cooked tidbits for your consumption. Enjoy.